Needing to be up at oh dark hundred the next morning, I improvidently began Ira Levin’s The Boys from Brazil, a mesmerizing thriller involving “creating” a certain type of child by mirroring his environmental and genetic makeup. No spoilers–the plot twists and turns like a racetrack–just this advice: if you’re attempting a half triathlon next day, you would do well not to begin this book after your pasta dinner. You will end up exhausted enough without plunging into the water on three hours sleep. Because Levin doesn’t tell you who the bad guys are trying to recreate (by murdering seemingly disparate men) until half-way through the novel, the volume remains the poster child for “you can’t put it down.”

But my essay this week is about neither triathlons (notes to self: South Florida boys don’t function in 63 degree water in Northern Europe) nor staying up all night with a good book (nothing better.)

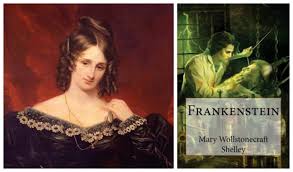

Instead, this blog is about how trying to create the children that you think you want very likely leads to the children that you actually don’t want. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is the creator, not the monster. You don’t want to be him either.

The slipperiest of slopes goes from a) giving advice to b) influencing to c) creating. Let’s begin with insisting that your young adult child not marry Stevie. Don’t get me wrong. I too find every aspect of Stevie’s appearance, personality, and character appalling and unacceptable. Did I mention that Stevie tried to run me over with their piece-of-dreck car? Not only is Stevie from the wrong family, an adherent of the wrong religion, but Stevie is also not the gender you would have preferred for your kid. To be clear, on the list of people for whom I would cheerfully die, Stevie‘s name does not appear at the top.

But for whatever reason, there is your young adult child making Moon Pie Eyes at Stevie, talking about the future, discussing table settings and hors d’oeuvres. And what do those ensuing years entail? The adults in the room feel posilutely certain that subsequently your child’s conversation with Stevie will include the phrases “double wide,” “emotional and economic bankruptcy,” “desperation,” and “Mulligan.”

Would you rather be right? Or would you rather be happy? You are unlikely to have your Kate and Edith too. Stated another way: either your young adult child ends up happy with Stevie—in which case opening your mouth was brutally ill-advised. Or your young adult child is unhappy in which case elucidating the obvious is just mean. I don’t know about you, but when I wake up in the morning, I want my options to be better than either wrong or mean.

“You’re right, dad. Stevie is the wrong religion, wrong social class, wrong gender. Thank you for pointing that out. I will now fire the caterer; Stevie and I will break up post haste.” Words no human ever spoke.

How bad could this situation get? You could refuse to go to the wedding. You could hold a funeral for your child. You could tell all your relatives not to allow your child connection or support. Rejecting your children because of their bad “choices” is as tragic as it is common. (I would not presume to tell you how to spend your Sunday afternoons, but if you refuse to attend your gay daughter’s wedding, don’t wait by the mailbox for a card on your anniversary.)

Replace “low-rent, pimply-faced, NOCD,* Stevie” in the above paragraphs with “the choice of undergraduate institution” and you have yet another reason to remember that the four most important words of parenting are “shut the #%*$&@! up.”

Because while you might feel strongly that your child belongs at Duke, Harvard, or Stanford rather than North Cornstalk State, your child—who will be attending the actual classes, taking the actual exams, and writing the actual papers—may not share your perception of their ability and motivation. Your child may have a strong opinion about fishes and ponds.

Ultimately it is your child who is choosing a marriage partner or an undergraduate institution. “The hardest thing about Harvard is getting in” is a cliche suggesting that students in Cambridge typically do well. I would argue that an even harder thing about Harvard would be flunking out. Your child knows better that their parent whom they love and how much they are willing and able to study. Yes, it might take some time to come to terms with the phrases “my child attends Hugga Mugga Community College” or “my child married neither a Cabot nor a Lodge.” Get used to it. Because the alternative—being either wrong or mean—is not a book that anyone will stay up all night to read.

* Not Our Class, Dear