“You never know” suggest the strategists tasked with separating you from your dollar. Those designing lottery adverts are compensated by their success. “You never know” is an enticing campaign. The implication—that you might win a million dollars and be able to significantly pay down your credit card debt—is clear. You never know. Somebody wins.

Simple arithmetic suggests, however, that the actual somebody will be somebody other than you.

Line up the following books on your shelf: James Joyce’s Ulysses (265,222 words); Bleak House by Charles Dickens (360,947 words); Tolstoy’s War and Peace (561,304 words) and Anna Karenina (349,746 words); Melville’s Moby Dick (206,052 words); Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte (183,858 words); Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility (126,194 words); Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath (169,481 words); and One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Marquez (144,523 words). Grab 10 copies of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird. (You want to have one to give to each of the grandchildren! 100,388 words times ten copies comes to 1,003,880 words.)

Pick a word at random from any page of the assemblage of 3,371,207 words. The likelihood that you have chosen the “winning” word is still significantly less than the chance of buying the winning lotter ticket–one out of 22,957,480.

It could be argued that spending a dollar on the Florida lotto each week has an upside. I have no problem with a dollar’s worth of fantasy: We could support a women’s sewing cooperative in Sub-Sahara Africa! We could set up a tutoring program for economically disadvantaged third graders in our community! We could multiply our charitable contributions by a thousand! Nothing wrong with tossing away a buck, a bargain as fantasy purchases go. A dollar a week won’t cause any of us to miss a meal. Of course, none of my sensible readers would purchase 1800 lottery tickets every week for three years.

Or would they?

Private law school tuition is approaching $70,000 per year. Assuming students wish to live indoors and consume the odd bowl of porridge–aka room and board–being graduated with $200,000 of debt is a thing. Admissions officers as private law schools, like their counterparts in lottery promotions, are unlikely to suggest that your samoleans could be better spent elsewhere. Similarly, there is a sign in the casino advocating that those with a gambling problem should get help. Have you seen that sign? Neither have I.

Private law school and concomitant debt could work–if your kiddo lands one of those $200,000/year gigs upon graduation. That $200,00 figure is not a typo. There is a small number of twenty-six-year old kids earning $200,000/year. To be fair, these opportunities are two actual jobs—one that pays $100,000/year and runs from seven in the morning until three in the afternoon and another occupation with an additional $100,000 in compensation beginning immediately at three in the afternoon finishing up around eight at night plus all day Saturdays. Yes, it’s a lot of money. In exchange for quite a bit of lawyering.

Which is a choice a reasonable young person can make. I need a nap just thinking about all those hours frankly, but nobody asked me. My concern is the recent grad, now pushing 30, saddled with untenable debt. Her options are limited. She cannot do public interest law; she cannot follow her heart and work for the public defender—with a $47,000/year salary at the PD, she can’t pay the interest on her loan, never mind buy a home, start a family, save for retirement; she can’t do anything other than grab that $200,000/year golden ring, mortgage her soul, and go to work.

Except, of course, not everyone gets the prime job with the astronomical compensation. Top law firms don’t pay top money for non-top students. Garrison Keillor was being ironic when he suggested that all students are in the top 10%. Not to mention arithmetic twice in one article, but not everyone can be at the top of the class and score that $200,000/year position.

Choosing the wrong law school reminds me of the game of chicken: two cars hurtling toward one another at unsafe speed. The loser driver is the one who turns away avoiding the deadly crash. Henry Kissinger, making an analogy to nuclear deterrence, suggested the winning strategy: rip out the steering wheel, wave it out the window so the other driver can see it, then hurl the steering wheel away from the car. When the other driver knows that his opponent cannot change course, he must choose to turn off. Stanley Kubrick, George C. Scott, and Peter Sellers explained this concept more succinctly in their 1964 film, Dr. Strangelove or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

It could be argued that being graduated from a private law school with crippling debt isn’t as bad as mutually assured destruction and the flaming end of all sentient life on the planet. But there are some vague similarities. Go big or go home. If our daughters do go to the expensive private law school, they better be “all in.” Failure is not an option. But, by definition, some number of students will fail. (And don’t get me started about the kids who flunk out; they have unsustainable debt and no earthly way of earning enough to pay it back.)

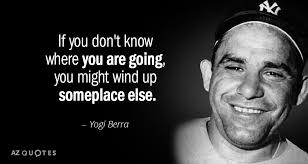

How can loving parents determine, in advance, whether or not their child will be one of the ones at the top of her class for whom $200,000 in debt is a path worth considering? Perhaps a more insightful author than I might have some insight. As Yogi Berra pointed out, “It’s hard to make predictions, especially about the future.” For now, all I can say is that the consequences of being wrong about private law school are severe. Buying a lottery ticket for a dollar is more than reasonable by comparison. It’s critical to know the odds before walking into the casino. And walking past the casino is frequently the better plan.