To ensure a healthy harvest, the townspeople are careful to get the sacrifice exactly right. Apparently there were imperfections last year: the dress was not sewn properly, the sandals were open-toed. As a proximate result, the rains came late. This year the elders are determined not to make the same mistake. The ceremonial shrift will be the proper shade of white, will come down to exactly six and a half inches below the knee. A few generations ago, the gown was exactly right, and the result was ideal—bushel after bushel of healthy crops. This year a properly attired young woman will be thrown into the volcano.

Meanwhile in another locale and a different time, parents are determining what their daughter should do. How much of her junior year should be devoted to cross country running, how much time should she spend perfecting her ability to shoot skeet, how many hours should she devote to learning how to pilot a small airplane. The young woman has scant interest in scampering, target practice, or aviation. She would prefer to focus her high school years on designing, writing, and editing the yearbook, a production about which she is passionate. Her parents have vehemently discouraged literary endeavors. Yearbook editors don’t get into selective colleges, they argue, whereas pilots do. This author supposes being compelled to be an aviator is preferable to being pushed off a ledge into molten lava.

The deity Goodcollege must be appeased.

The Villagers—that is to say the parents in the high school parking lot—can almost be overheard: Susie took piano lessons since she was five and was rejected from Duke, but Swoosie studied ballet from the time she was six and was admitted to Stanford. Timmy was president of the senior class and was denied at Northwestern, but Tommy was president of the whole school and got in to Dartmouth.

And I did jumping jacks in my pajamas in the middle of the street at midnight. As a result, there are no llamas in my kitchen.

Among highly qualified applicants, admission to highly rejective colleges is a random procedure. Explanations abound about what happened and why—after the decisions are made. It is much harder to determine causality ahead of time–to know that Swoosie and Tommy would be favored over Susie and Timmy.

None of which is to blame good-hearted parents from trying to unravel what is essentially an arbitrary process. I would be pleased to know what the stock market will be doing in the future or who will win the super bowl next year. But I’m not going to devote my time, attention, treasure, and the childhoods of my progeny focusing exclusively on where they’ll be admitted. And I am certainly not going to berate my kids, their teachers, or their schools should the children end up at Dickinson rather than Princeton. I’m going to focus instead on helping them acquire the skills that will allow them to be successful in the classroom and in the dorm wherever they end up. You were rejected from the University of Michigan, it’s the end of the world as we know it makes as much sense as yelling at the dice. And unlike the craps table, our children have feelings.

Moving from real to imagined victims, can we talk about how selective colleges are discriminating against absolutely everyone. Students from families of privilege are not getting in anywhere because of affirmative action. First generation and underrepresented applicants are being rejected in favor of wealthy kids. Kids from Gulagistan have no chance because all the spots are given to students from Thrace. And applicants from the esteemed ancient civilization are rejected because all the offers are given to Gulagistanians.

It’s a wonder these campuses have any students at all. What with everyone being rejected in favor of everyone else.

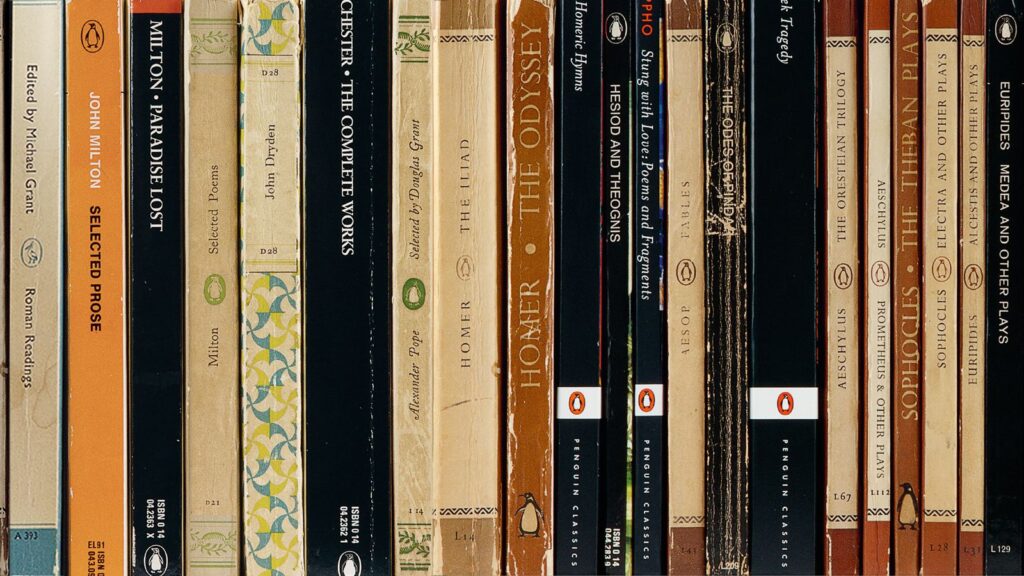

Meaning no disrespect to the supreme court, newspaper reporters, and parents in high school parking lots everywhere, could we change the conversation. Imagine if instead of worrying about the odds and opining about admit ratios, we instead discussed books with our kids. Last I heard, books were a relevant part of an undergraduate education. Can you conceive of a student who had already read all the assignments for the first-year composition course the summer before going off to college?

That’s the student every professor wants in their seminar. Assuming the kid hasn’t instead been pushed into a volcano.