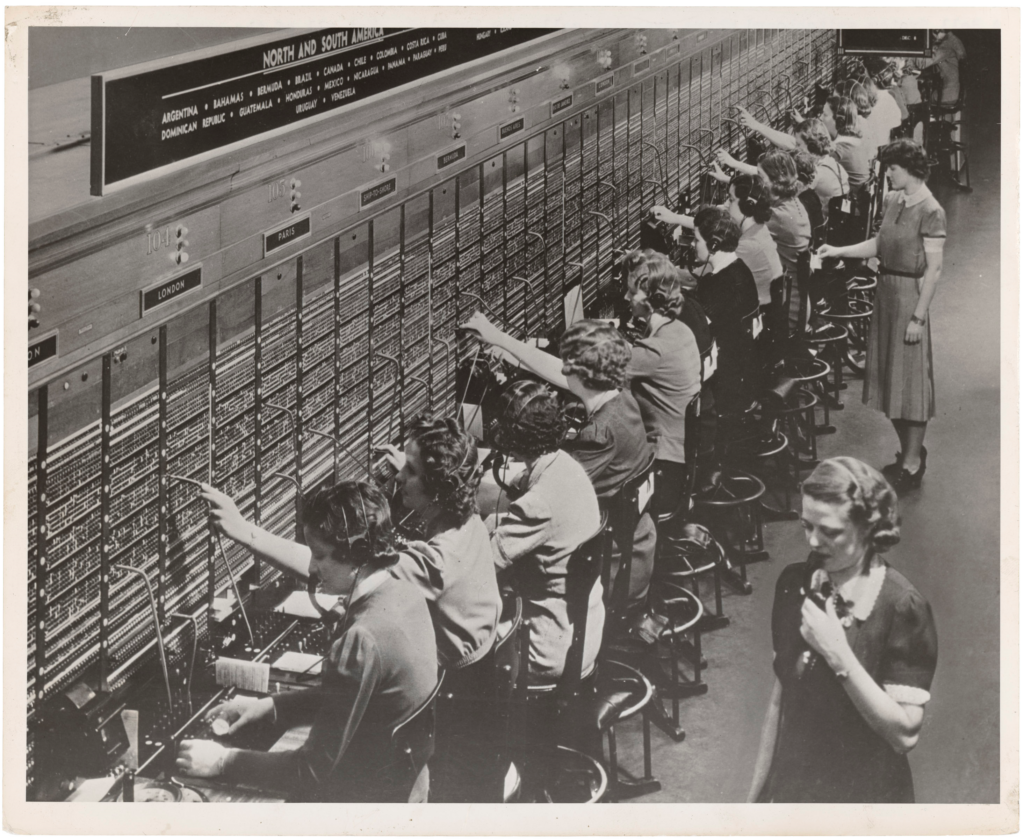

One of our running buddies is an administrative assistant. Her skill set and her previous experience encompass managing every aspect of an office. In these Covid-permeated times, her responsibilities have been curtailed to endless scheduling, which is fine, a job is a job. Her new responsibilities are limited to taking phone calls and arranging appointments. Terrified patients call. Our running buddy talks them off the proverbial ledge and sets them up with potentially life-saving engagements with one of the dozens of neuro-surgeons in the massive hospital complex.

What is of interest is the inverse relationship between the compassion that she can communicate to the apprehensive callers and the way her job performance is evaluated. Every time she articulates human concern—“I’m sorry to hear that,” “of course we’ll take good care of you,” “anybody would be scared”—her supervisor takes note of the “lack of efficiency” with which she handles her calls. Her evaluation has a space for “calls per hour;” there is no line for “helped patient understand that she is a human being.” Our friend’s job is to “put heads in beds” not to help patients understand that having their skulls cracked open and their brains rearranged might be frightening.

I have no insight into hospital budgets, salaries for neuro-surgeons, or pay scales for administrative assistants. I’m just noting that something is lost when the extra minute to convey kindness and concern is a bad thing.

Examples of the negative correlation between speed and effectiveness abound: “Time takes time” as we say in recovery. It’s unrealistic to expect a lifelong commitment to sobriety after 72 hours without using. Folks on the path back from substance use disorder have to experience what it’s like to wake up enthusiastic or bored, calm or nervous, committed or wavering. Every day is different and has to be considered individually. “One day at a time” means take each day as it comes. But “one day at a time” also means experience each day as a new way to deal with the ups and downs of being sober. Each day will present new challenges.

Our running buddy’s frustration with being discouraged from displaying empathy also reminds me of the way some parents expect “performance” from their children without allowing time for connection. Parenting experts talk of “quality time” with children. This author is not a fan of the concept. Sensitive as I am to how hard folks work, there is something to be said for family dinner, family game night, family let’s-sit-on-the-couch-and-not-talk-about-anything-important night. Even if work schedules and fear of bears preclude family camping weekend. Focusing only on performance—good grades, a clean room, a polite response—takes something away from the interactions that have defined out species for thousands of generations.

Runners know that an accelerated schedule leads to injury and failure. To complete a marathon, long training runs are necessary. “I didn’t have time to run 20 miles slowly, so I ran five miles fast.” Glad to hear you had a pleasant morning, but don’t plan on being able to get through 26.2. The only way to complete a marathon without your body breaking down into hundreds of unhappy pieces is to take the time to work up to running 20 miles in training.

The best spaghetti sauce needs time to simmer; the best parent-child relationships need time to evolve; the most effective training plans need time to develop; sobriety takes time to reify. In a perfect world—even a decent world—our running buddy would be able to take a few minutes to reassure her patients that their impending surgeries are concerning and worth talking about. Fortunately, your relationship with your child is not governed by a supervisor with a clipboard. Take the time—starting today—to focus on the long game with your kids.

One thought on “T-i-i-i-m-e”

I want immediate gratification and I won’t wait one more second!