I find it hard to relate to Superman. By definition, after all, he is a man. His powers—flight, x-ray vision, impenetrable body—are totally cool, but not those you’d expect to find particularly useful if you weren’t making Metropolis safe from diabolical types. Superman can do anything, has no limits, can even run so fast as to reverse the direction of the Earth and make time go backward. He’s most accessible, I would argue, when he is inept around Lois Lane. A metaphor for men in the 50s, perhaps.

Batman is darker, more complex, more interesting because he relies on sleuth and cunning, has more foibles and vulnerabilities. It’s fun to think of being a millionaire playboy, of having unlimited access to cool equipment and hot girls.

But Spiderman is more enduring, more relatable. Because his powers are limited? Because he’s human and could—in theory anyway—be harmed by an ordinary bullet? Because he’s tortured? If he had only stopped the burglar in Amazing Fantasy # 15, Spiderman’s beloved Uncle Ben would not have been killed. Do adolescents love Peter Parker because–for the first dozens of issues anyway—he comes close to but never gets to kiss Gwen Stacey?

If only I didn’t have to change into my uniform and deal with The Vulture (issues 2 and 7), Dr. Octopus (issues 3 and 11), The Lizard (issue 6 and 44), The Shocker (issue 48), and all these other super-baddies! Were I free to explain to Gwen who I am, then I’d show you some smooching you wouldn’t soon forget.

I think being socially inept and unable to communicate his real self to girls is part of our attraction to Peter. But as a devoted Peter Parker aficionado lo these past 50-something years, I have an additional explanation for his enduring attractiveness. (A copies in superb condition of the first issue from the early 1960s sells for hundreds of thousands, sometimes millions, of dollars.)

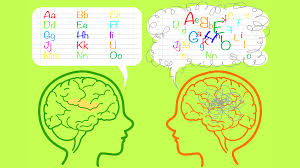

Peter’s inability to show up, to be there for his girl, to attend class, to get to his off-campus job is a metaphor for our learning differences.

Now before we have spun our first web, there is an obvious objection: Peter himself is a star honor student, a great scientist. There is nothing in the text to suggest that there is anything non-standard about how his neurons are arranged.

But listen to what adolescents who have not been bitten by a radioactive spider have to say about their inability to get their homework done, to perform up to their ability, to stay organized, to write down their assignments in their organizer.

I was planning on studying. But my friends needed a fifth for basketball. I was going to get started writing that paper, but I wanted to win one more level of Shoot, Shoot, Shoot, Blood, Blood, Blood, Kill, Kill, Kill. I meant to go to the extra help session for math, but I slept in.

To say nothing of the trouble our kids have trying to attend to the lectures when they are overwhelmed with the sound of the water fountain down the hall or worried about their performance. A little anxiety helps us stay focused. Overwhelming anxiety leaves us unable to be productive.

Peter Parker has an excuse for why he can’t be present to date girls. He desperately wants to but is called away by his responsibility to keep the neighborhood safe, to do the right thing. Students with learning differences, attentional issues, or executive functioning limitations want to study but are distracted by their imperfect brains.

Nobody wants to be the kid with the learning differences, with the consimitant underperformance. With great power comes great responsibility. With a good brain but a distracted one comes the likelihood of being misunderstood, singled out, excoriated. Telling your children you’re so smart, if you would only focus, you would get all As is as effective as telling Peter Parker not to leave his potential girlfriend to go fight super-powered bad guys.

Spider-man can’t communicate who he is. His identity must remain secret so his loved ones are not taken hostage or harmed. Children with learning differences can’t articulate what their needs are if their parents are neurotypical and unsympathetic.

I don’t know exactly what I would do to help Peter Parker. He’s not my client and is, after all, fictional, the creation of the lamented Stan Lee. But I do have a recommendation for parents of children with learning differences: Take your kids at their word. If they say they are having trouble concentrating and attending, help them develop strategies. Don’t bludgeon them with vacuous admonitions to try harder or ineffectual punishments. Help them identify, accept, and articulate their learning differences.

Maybe your beloved children won’t learn to stick to walls or swing across town on webs, but they will certainly be more comfortable and more successful in their own non-costumed skins.