I want to clarify what I mean when I write, “after you have kids, it’s no longer all about you.” The other side could be–has been–argued. What about the needs of the parents? Isn’t it the moms and dads whose well-being should take precedence? Aren’t the adults supposed to put on their oxygen masks first. And what about the fifth commandment, isn’t Exodus 20:12 pretty clear? Who is supposed to do the honoring around here anyway? Don’t the spoiled-rotten, decadent, out-of-control, overindulged, snarky children come from families who focus on the children’s every wispy desire rather than insisting that the kids be respectful, do as their told, be seen and not heard, and unload the dishwasher already how many times do I have to tell you?

Kids want to do that which is contrary to their best interests, don’t they? Left to their own devices, would children ever eat their vegetables never mind do their homework, let alone take the trash buckets out to the street on Monday. Kids want to ride in limos when they’re seven years old, eat ice cream for breakfast, stay up past their bedtime, have unprotected pre-marital sex. Kids want to do that which is age inappropriate. The only way to stop adolescents from drinking and driving is to put them on a short leash. The kids need to be more scared of their parents than they are eager to impress their zit-encrusted, know-nothing, out-of-control, ignoramus peers. The “pressure” in “peer pressure” comes from those other dimbulbs offering our children recreational drugs and ignorance.

Nah.

Kids know why their parents are telling them what to do. Even a stray dog knows whether she has been tripped over or kicked. Parents who just want to brag about their kids being obedient and sucessful don’t do as well as parents who want what’s best for their kids for their kids (not a typo). Parents who make the hard sacrifices on behalf of their kids get the kids who respect, obey and out-perform. An example based on a factual family history may emphasize the point.

As my long-time readers know, my father’s father was murdered when my dad was two months shy of his sixth birthday. My dad grieved that loss for the next 89 years. Until he died a few years ago at 94.

My grandfather, by all accounts, was something of a low-level criminal. I’m not judging. Times were tough. But the man seldom did an honest day’s work in his short life. Not that life was easy for trustworthy people either during the depression. My grandfather was driving a beer truck illegally—all beer trucks were against the law in 1929 at the heart of the 13-year reign of the 18th amendment—when some other felonious yabo jumped onto the running board. And shot my grandfather in the head. His body, presumably somewhere in the swamps of Jersey, was never found.

The tough times for my grandmother’s young family got tougher. As I’ve shared previously, she took her kids, five and three, to turn them over to the state-run orphanage only to change her mind at the last minute. It is still not clear to me almost a hundred years later how she sebsequently managed to feed those kids.

But this story is about the sacrifices of my father, not the suffering of his mom. Somehow my dad got enough to eat, got in and out of the army, got through law school on the GI Bill, met my mom and had a couple of kids of his own by 1959 when this narrative now continues.

In addition to learning how to peel potatoes for 14 consecutive hours and shoot a machine gun from the plexiglass ball turret under a B-17 in the army, my dad also figured out how to smoke cigarettes. Apparently he got pretty good at it because by the time my sister and I appeared on the scene he was up to three packs a day. He would line up 60 cigarettes on his desk each morning and smoke every one before taking the bus home to his young family.

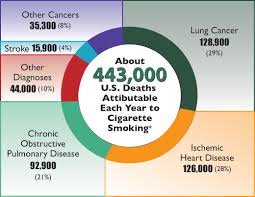

Don’t let anyone tell you that the relationship between cigarettes and cancer was “discovered” in 1998 when Big Tobacco was ordered to pay 206 billion dollars to offset the public health debacle from which they were linearly responsible. My dad and the rest of the smokers in the 1940s used the term “cancer sticks” advisedly. Everybody knew cigarettes caused cancer. Everbody knew cigarettes were addictive. It just took a few decades for Phillip Morris and RJ Reynolds to pony up to the truth and cough up (sorry) some samoleans, 206,000,000,000 of them.

And my dad was addicted to cigarettes with the best of them. Again, three packs every work day, more on the weekends. He lit his first cigarette after he brushed his teeth first thing in the morning, smoked his last one just before bed.

Here’s my understanding of what happened when I was three years old: My dad reflected on how brutally unpleasant it had been to grow up without the economic and emotional support that his father might have provided. He determined that he wasn’t going to check out early. No driving a beer truck. No low-level criminality. No cancer sticks. My dad intended to be around to see his kids get through grad school, toss a ball with his grandchildren.

So he quit. Cold turkey. December 5, 1959. He never smoked another cigarette for the rest of his days, 59 more years of them. Although he freely admitted to missing cigarettes each and every day for those 59 years. Addiction is addiction and craving is craving. No fun. My family celebrated the anniversary of my dad’s quitting cigarettes more joyously than we acknowledged my parents’ wedding anniversary. Because as my dad pointed out, “anybody can stay married for 63 years.” But getting free of nicotine is a healthy lung of a different color. Some folks stand up and make the brutally tough choices. My dad was one of those folks.

That’s what I mean when I say that once you have kids, it’s no longer all about you.

So what am I asking you to do or not do? Not a thing. I am not the morality police. And I don’t know everything about where healthy families come from. I would not presume to suggest that you come home from the bar, the office, or the motel to play Parcheesi with your kids. You are certainly entitled to “find yourself,” “get out of the house,” “take some time.” There’s no stick her.

But they may be a carrot. If you do make the hard choices—make a little less money, make it work with your imperfect spouse, give up cigarettes–your 68-year-old kid might be writing you a thank you note in his weekly blogs six years after you’re gone, reminding his readers how a good man lived, the choices he made, the sacrifices he endured..

Thanks dad. I appreciate your contribution in WWII; I appreciate your sacrifice in giving up your beloved cigarettes; I especially appreciate not having to schedule you for a tracheotomy resulting from your cigarette-caused throat cancer. And I especially appreciate all those raucous, trash-talking, outrageous Parcheesi games. Miss them. Miss you.

Of course I can’t promise. But I like to think that your great-grandchildren with be playing Parcheesi with their kids long after I too have graduated to that unlawful beer truck in the sky.

Thank you for reading. See you next week.

One thought on “Skittles and Beer Trucks”

My dad was a B-17 pilot in WWII. Was shot down and a POW in Germany until the war ended. We were never “allowed” to ask him about his experiences growing up. It wasn’t until our oldest child was given an assignment in 7th grade to interview a veteran. He was very close to my dad and my dad agreed to the interview. That assignment opened up a whole new world to all of us…..the stories, the letters to his parents, the lingering thoughts about the experiences…..I could go on forever!!Dad was later interviewed by the POW museum, traveled to different schools to speak about his experiences and was given the opportunity to fly on a B-17 when it came to the Tamiami airport years ago with a few other WWII planes. We will forever be grateful for that dedicated teacher for the life changing assignment!! Keep up the good work David.