“Mother, Please! I’d rather do it myself!” suggests an as yet unmedicated home maker in an iconic 60s commercial. Mom’s transgression? Enquiring if perhaps the stew needs some salt. But, with the benefit of a half century of hindsight, this author wonders if mom’s suggestion was not the first of its kind.

You should be happy! Look at all you have! There are 30 million Americans out of work! You don’t have Covid! Be grateful! These are all bad arguments, unlikely to be effective. Nobody ever felt better as a result of being told to do so. Children especially, do not want to be told how to feel. A spent light bulb can be replaced with a new one. Whereas a child’s feelings cannot be ameliorated by direct instruction, the ubiquity of this parenting strategy notwithstanding.

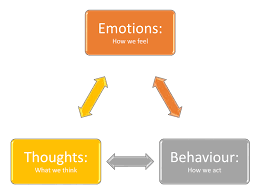

Behaviors can be addressed by fiat; feelings, not so much. Big people can force their kids to do pretty much anything—take a “no thank you bite,” for example—but the feeling behind the behavior—“I don’t much care for mashed liver”—is intractable. Hence the irony: understand the feelings underneath the behavior and the behavior may be amenable to improvement.

A request for liquid at bedtime is seldom about impending dehydration. May I have a drink of water? is more likely about being scared of the dark or wanting another chapter of Winnie the Pooh or needing connection. Or something. Six-year-children are seldom actually desiccated. Understand the feeling—Lonely? Angry? Sad?—goes a long way toward making sense of the behavior—thermonuclear crying.

Everyone is entitled to our sympathy; everyone is entitled to our respect; everyone is entitled to our understanding. Kids in particular. Because most people are trying to do the best they can. We get into trouble when we make others out of the others. And then it’s easy to impugn the wrong motives. He’s just asking for a drink of water because he knows that I want to get off my feet for the first time all day and watch Shameless with my husband whom I haven’t spent ten consecutive uninterrupted minutes with in the four years since our child was born. Nah. He’s four. The simplest hypothesis is probably the best: he wants to hang out. Or he’s scared of the dark. Your four-year-old doesn’t know anything about William Macy.

Let’s make an extraordinary extra effort to understand our children in these crazy, virus-infused times. The alternative–lack of empathy, forcing the kids to behave, insisting that they stare at a teacher on a screen—might lead us in the direction of a populous in need of medication just to get through cooking dinner. Oh, wait: that’s exactly where we are. In the six decades since “Mother, Please! I’d rather do it myself!” Anacin has given way to Effexor and Ambien. Could understanding and compassion lead us away from pharmacological dependence? Let’s start with consideration and acceptance of our children. Let’s allow our loved ones to feel how they feel without coercion. Maybe they can be part of a next generation, a generation capable of cooking dinner without snapping at their relatives.