The Marshall Plan didn’t kick in until April, 1948. The war in Europe ended in May of 1945, giving people who had plenty of practice being hungry since 1939 a chance to perfect their ability to starve.

Supply chain issues—defined today as a failure to acquire a toy with the preferred microchip—was even more of a thing is countries who had been bombed back into the Stone Age. Roads? Gone. Railway lines? Nope. Trucks? Sure. But no tires or gasoline. So even if food had been available, there was no way of getting it to isolated folks. Millions of people went without sufficient calories to sustain life.

One mom remembered that the wallpaper in a nearby apartment had been stuck on with a potato-based glue. The roof of the building had collapsed as a result of the bombings but some of the walls remained standing. She stripped the wallpaper, boiled it, and was able to provide a life-sustaining broth for her children. It is hard to imagine 76 years later the level of privation. Soup made from boiled wallpaper.

Allocation of scarce resources has been a recurrent theme throughout history. To a first approximation, everyone was starving. Not just as a result of war, but from lack of refrigeration. There just weren’t enough calories to go around. Indeed, our current epidemic of obesity is rooted in our evolutionarily adaptive environment. Our cells evolved to store fat. Our ancestors didn’t know where their next meal was coming from. Or when. Hominoids who didn’t die between meals had an advantage

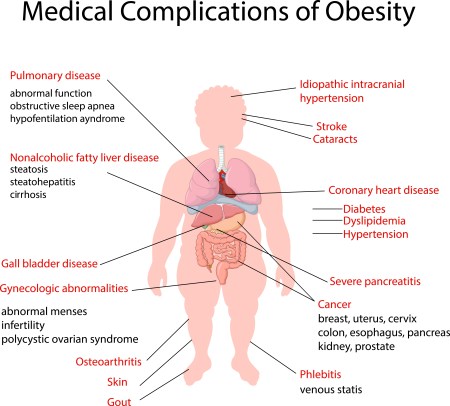

Whereas today, calories are as ubiquitous as spam. Never mind carbs. Bread, pasta, and potatoes are all just basically sugar. Big gulps, Slurpees, sodas, candy, cookies are everywhere. Unhealthy sugars are available all year, not just during the holidays. For the first time since our human lineage split from our common Australopithecine cousins two and a half million years ago, more people die of too many calories than too few. We are eating ourselves to death rather than dying from starvation. Calories are no longer a gift; calories are a health concern. “There are no old fat people” a health care provider pointed out. Obese people succumb to COPD, heart issues, strokes, hardened arteries. A hundred extra pounds means 20 fewer years.

Long time readers will hardly be surprised that there is an analogy coming relating the consumption of too many calories with educating our beloved children.

A large Slurpee has 570 calories and more carbohydrates than any human needs in a day. A high school student can take five advanced placement courses in her senior year giving her as many as 13 AP classes by the time she applies to college. Surely, if one AP class looks good on a college application, 13 AP classes looks better, the thinking among bright kids at academic high schools goes. So what if the kids are stressed to the point of snapping? Who cares if students fall asleep at one in the morning with the lights on and a book on their lap? What difference does it make if they sleep only five hours each night and are so exhausted that they can barely function during the school day? Won’t the sacrifice pay off when the children are admitted to highly selective colleges?

As a matter of fact, no. The sacrifice, after a point, is entirely misguided. As the president of Stanford University pointed out recently, 13 advanced placement classes are no better than five. To repeat: thirteen AP classes rather than five do not convey an advantage. Students who have 13 AP classes are sometimes admitted to highly selective colleges—last year Stanford admitted one applicant out of 20—but sometimes students with five AP classes get a lucky roll of the dice. Similarly, students with 13 AP classes are frequently rejected from HSCs. And to be fair, students with five APs are commonly rejected as well.

I am not insensitive to families who believe that more is better. In post war Europe scarcity was the overriding concern. But the college landscape in modern times is different. The vast majority of colleges admit virtually every qualified applicant. That stat was true when I started my professional practice in 1984 and remains accurate all these admissions cycles later.

Too many calories. Too many AP classes. Who would have thought that shortages of food and educational opportunities are no longer relevant? What a joy to live in a time when there is enough. Loving parents no longer have to scavenge for potato-based glue to feed their children. Sensible parents no longer have to search for educational opportunities for their kids. And kids should avoid overextending themselves as much as they should avoid a diet relying on chocolate cake, candy bars, and Slurpees.

One thought on “Eating Disorder, Part One”

Well said, thanks for sharing!