Kids have always wanted to be heard, don’t you think? Adolescents want to find their place in the world, find themselves, find out where they belong and with whom. And then once they have found that spot, they want to communicate their allegiance, participation, connection. Isn’t that what the dyed hair and involvement in social clubs is about?

But if my students were novels, their stories would begin on the last page.

Narratives used to have a “reveal.” That’s what kept readers reading. What’s the deal with Pip? With Huck? With Gatsby? With Tom (of Tom Jones, a rollicking good read now as it was in 1749)? What will we learn about their development, their growth, their arc?

What will the characters learn from the other folks in the book? What will they reveal about themselves as they mature? Huck learns humility and compassion from Jim. Readers learn Gatsby’s origin. Tom’s maturity, sensitivity, and insight is unwrapped as delicately as a sweater coming off the shoulder of his beloved Sophia.

Whereas my students tell everything to everyone in the first paragraph of their personal statements. Their eating disorders, their issues with substance abuse, their criminal pasts—there’s no reason to read to the end of the page. There is no story line, there is no build up, there is no “what comes next?” It’s all out there in the first few sentences.

Admission is the name of the game. Surely the personal statement is an opportunity to communicate more than is evident from course selection, grades, norm referenced test scores (for those few colleges that still aren’t test optional,) and letters of recommendation. But admission also means “a statement of acknowledging the truth of something.” That “an admission of guilt” is the standard example doesn’t mean kids ought to be talking about that which should be private.

There is something to be said for polite discourse. “My, what a lovely outfit” outscores “did you hurt yourself running away from good taste?” You wouldn’t write an essay about potty training. Why would you talk about throwing up after a meal?

Some aspects of a student’s record require an explanation. A coming-of-age essay can be appropriate and meaningful. My depression during the pandemic resulted in a D in Algebra II, is relevant to disclose. But I went to summer school, studied frenetically, and got an A in calculus is a reasonable conclusion. That was then, this is now; I was lost but not I’m found; I was blind but now I see.

Whereas there is no reason to explain when no explanation is reasonable. It is not necessary to disclose when disclosure is not necessary.

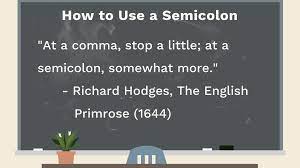

Thirty-eight years of editing student essays times ten or twenty students each year times a dozen essays per student equals four or five thousand essays. Here are two trends: 1) Nobody knows how to use semicolons anymore. 2) The lives of students are public. What they eat, whom they’re with, where they are, what they’re doing—it’s all out there. There are still doors on their bedrooms and bathrooms—thank goodness—but they have little privacy. So their desire to be heard has morphed into an understanding that they can never be quiet.

There are no bad topics but there are bad essays, Harry Bauld pointed out. Perhaps an update might include: just because you hear a donkey braying in a field, doesn’t mean you have to get down on your hands and knees and make raucous noises yourself. You are worthwhile as you are even if you haven’t suffered egregiously. And if have had something special or especially unpleasant, you don’t have to mention it in the first paragraph. You are worthy of respect even if you haven’t been to rehab or to jail. And the less you try to invent and explain that you are worthy of respect, the more likely you are to get it.