Mr. Smith has been convicted of a particularly heinous crime. A jury of his peers has found the testimony against Mr. Smith to be unassailable and damning. The witnesses were unanimous regarding the evidence presented. Three nuns, the mayor, and the principal of the local high school all witnessed Mr. Smith’s egregious act as did three video cameras. Mr. Smith has confessed—repeatedly and unwaveringly. Mr. Smith is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. Mr. Smith is guilty beyond any doubt whatsoever.

Before passing sentence, the judge asks if anyone would like to speak. Mr. Smith’s mother stands up in the crowded courtroom. “My son is such a good kid,” she says. “He would not have done that.”

If the longest journey begins with a single step, how did Mr. Smith get from the maternity ward, filled with hope and promise, to a life sentence without possibility of parole? Did Mr. Smith’s previous bad acts cause his mother to be an enabler? Or were Mr. Smith’s repeated lapses responsible for his mother’s repeated rescues?

One school of thought suggests that children be punished, that reprimands instill respect and fear. I smacked my child’s hand when she tried to take a cookie. She hasn’t made that mistake again. Except not all children internalize the lesson. Children learn what they live. Kids who get hit grow up to be hitters themselves. Fear begets fear.

The other side of the straw argument suggests that we insulate our children from every sling and arrow. He can’t serve a detention. I don’t care what he did. I promised him we would go for ice cream if he agreed to attend school today. Clearly this mom is borrowing against a debt that she will not be able to repay. A detention can certainly be a teachable hour.

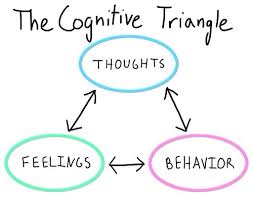

Neither side addresses the issue of bringing up moral kids correctly. The dispute isn’t about coercion versus permissive. The fundamental question is about understanding. Knowing why your kid has her hand in the cookie jar—hungry, angry, lonely, tired? —will address subsequent behavior better than punishments or rewards, controlling or permissiveness.

Similarly, telling your kid he’s better than he is will lead to the wrong place. As will telling you kid he’s no good. Rescuing your child is a mistake. But so is letting the child “suffer the consequences” without parental understanding or support. The answer lies not in what actions you take but in how you feel. Your attitude toward your child—unconditional love irrespective of his actions—allows the child to grow up feeling heard. He knows the difference between right and wrong. He will choose the proper path understanding that he is known for who he is.

Lots of Mr. Smiths come from families who enabled, rescued, and softened every blow. These Mr. Smiths never suffered any logical consequences. Their parents believed their kids no matter how unlikely the prevarications: the pot in my backpack wasn’t mine; I was just holding it for a friend. Or, I did my homework, but I left in on my desk at the house. (It goes without saying that neither of these statements is ever true. The marijuana in the backpack always belongs to the owner of the backpack. The homework was not done.)

But lots of Mr. Smiths come from families who were all about punishments. When he got arrested for using pot in 10th grade, we let him sit in jail overnight. When he got arrested for selling Xanax the next year we let him go to prison for 30 days. When he got the life sentence for killing his dealer and stealing that money, we didn’t even bother going to the trial. We didn’t spare the rod when he was growing up; I guess we should have hit him harder or more often.

Understanding the why of the behavior is invariably the proper step in determining how to help kids grow up healthy and whole with an interior compass that helps them choose the right path. Every child knows not to lie about homework; every child knows not to take drugs; every child knows not to deal drugs; every child knows not to harm other people. Loving parents help kids figure out why they are behaving improperly. Loving parents get to the feeling underneath the behavior. Are kids feeling bullied? Do they self-medicate because they are lonely? Do they take drugs because they want to fit in? Are they physical because they don’t know a better way to communicate? Are they violent because they are modeling what they have learned?

Ladies and gentlemen of the jury, have you reached a verdict? is many years, many decisions, and many opportunities too late to be saying, But, he’s such a good kid.

2 thoughts on “But He’s Such a Good Kid”

Beautifully expressed, extremely valuable message David, thanks for sharing!

Another great one! Keep ’em coming!