I could not help but overhear one of my neighbors having a lengthy dispensation with their 40-pound, brown, boxer mix: “We’ve spoken about this before, Ignatius,” she began. “How many times do I have to tell you not to pull so hard on your leash? You know I hurt my arm in the garden the other day. No, I’m not saying it’s your fault, I know you were just chasing rabbits and didn’t intend to tear up the vegetable beds. Just the same, could you please not pull so hard, Ignatius? My physical therapist charges a hundred fifty dollars an hour and we have that trip to the mountains coming up.”

There was more. But you get the idea.

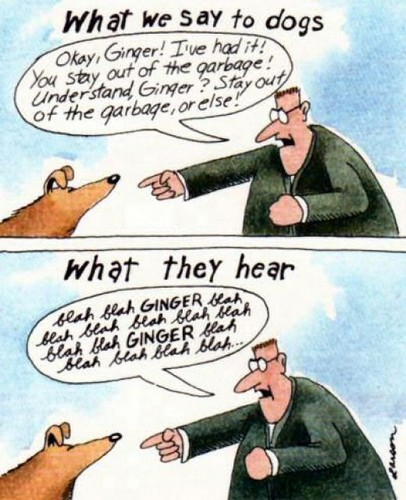

I thought of Gary Larson’s insightful take on canine communication.

Not to brag, but my dog understands what I say–sit, stay, heel, come–and, on a given day, follows those suggestions. Four words. Seems reasonable.

Which is not to suggest that your children need one-word commands. Only that if you don’t know what you’re communicating, you’re kids don’t either. Mortgage the farm.

For example: “Percy, stay out of the street, get back on the sidewalk, be careful, did you look both ways, a car could come by any minute” is more likely to convey the anxiety of the parent more than any actionable advice to Percy who–like Ginger in the cartoon above–stoped listening at the word “stay.” Percy may be five years old, but can perceive unequivocally that:

- there are no cars for blocks around

- there pretty much never are cars in the isolated cul-de-sac in which he resides

- in the rare instance in which a car appears, said vehicle is traveling at eight miles an hour, could see him and easily stop safely and have a pleasant chat with Percy and his parents.

None of which would be important. Staying out of the street is certainly a valuable skill. But Percy is going to develop selective hearing by the time he turns six and critical information about drinking and driving, reproductive biology, and where to attend medical school is likely going to be unheeded. Remember that story about the busy villagers who don’t show up to help the annoying shepherd? There’s a reason that tale has survived for two and a half millennia. (Don’t you wish you got the royalties?)

FBI agents are taught not to draw their weapons unless they intend to shoot and not to shoot unless they intent to kill. Which might be an inappropriate analogy for a column about parenting best practices, but your kids have to trust that their parents say what they mean and mean what they say and aren’t just blathering on because they are enamoured with the sound of their own pontifications. Brevity is not only the soul of wit but also good advice about ensuring that your kids will listen when you have sometime important to say. Because they know that when you do give a command that it’s likely to be relevant.

Hopefully, commands are only a small percentage of your communication with your beloved children, a distance second to conversation, inquiries, and quiet times. But you didn’t name your kid Ginger. Try not to blather on about that which makes no sense, isn’t important, and is more about your worries than what is relevant to your child’s experience.