Our understanding of and treatment for substance use disorder has evolved over the past half century. Moral failing and weakness of will were where we started. Imprisonment, punishment, and public humiliation were supposed to cure craving. Blood letting is a comparable example of the cure being worse than the disease. Talk about “the beatings will continue until morale improves.”

Poor people from “bad” families succumbed to the allure of marijuana. Rich people from “good” families “knew their limits” and only occasionally pissed themselves at the country club and drove off the road destroying hedges and families.

Screaming at and punishing people to discourage drug use makes as much sense as yelling at people to encourage them to relax. “Chill out, dagnabit!” Hitting a child to encourage gentle behavior doesn’t work either. A concise 60s slogan read: “Fighting for peace is like f***ing for chastity.

Note that the illegal drug users of the past hundred years were predominantly from marginalized communities. Or as a more insightful researcher than I noticed, “Black kids do a drug called crack and go to prison; white kids do a drug called cocaine and go to rehab.” Nkechi Taifa points out that the inspiration for the war on drugs was marginalizing Blacks and the anti-war left.

So “drug users are bad people” turned out to be something of an unhelpful exaggeration. Not when Nixon’s domestic policy advisor, John Ehrlichman admitted the racially motivated origin of the war on drugs. Especially when the users of opioids, cocaine, and Xanax turned out to be middle class and pale-skinned.

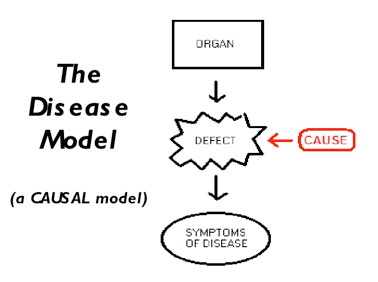

So, if “drug users are bad people” wouldn’t fly, the next step was “addiction is a disease of the brain.” “Addiction is a disease of the brain” was certainly an improvement over drug users are morally repugnant, pleasure-seeking, drooling, fatuous, child-like nimrods who deserve to be imprisoned, institutionalized, and lobotomized not necessarily in that order. And “addiction is a disease of the brain” had the advantage of positioning substance use as something that “happens” to unfortunate folks rather than that murky business of “choice.”

So those of us in rehab-world could suggest, “the best way to stop is not to start” (which I still believe) and “putting three quarters of a million dollars, a wife, two children and a five-bedroom home up your nose” could happen to anyone. Kevin McCauley makes an articulate, convincing case for addiction as a disease of the brain. His argument—that the brain only gives up its secrets grudgingly—resonates. Dr. McCauley explains craving—not fun—and likens substance use disorder to cancer or diabetes, a disease that befalls an hapless person, rather than something anyone would choose.

Of course, it would be useful to discern who gets addicted and who doesn’t. Some folks come home from the hospital after major surgery with 20 oxycodone and end up flushing 19 of the pills a few years later after finding the leftovers in the medicine cabinet. Whereas other folks say to that first puff or pop, “where have you been all my life?” and devote themselves ever after to chasing that first high. There’s a story about someone who had substance use disorder so bad that he deliberately got into car accidents, intentionally breaking his legs do that he could get more pain meds.

Addiction may be a disease, but the distinction between who is likely to get infected and who ain’t may have a lot to do with who the folks were to start. The most often quoted addiction studies have to do with rats.

- A rat in a cage has an electrode implanted in his brain stimulating the pleasure centers similar to the ones engaged by drug use. Pressing a lever excites that part of the brain. Soon the rat would rather press the lever than eat food or have a cuddle with a rat of the female persuasion.

- A rat in a cage is offered clean water or water laced with pain killers. The rat prefers the tainted water. Before long the rat favors the spiked water to the point of ignoring food in favor of getting high.

In both studies the rat would prefer the electrical stimulation or the drug laced water to the point of ignoring food or sex. The rats kept pushing the lever until they starved to death.

Also note however that both of these studies involve solitary rats in small cages. When the rats were hanging with other rats in a stimulating environment—“rat park”—the rats preferred the rodent equivalent of sobriety. Given the choice, the rats would rather schmooze with other rats in a pleasant environment running along Rat Beach and taking long romantic walks in Rat Disney World. The take-away is that human drug users are more likely to be those who have experienced developmental trauma. At the risk of gross over-simplification, humans who have been emotionally abused in childhood are more likely to seek out, rely on, and be addicted to drugs as soon as they are old enough.

“The opposite of addiction is community” as Dr. Gabor Mate eloquently explains. People who have meaningful connection are less likely to use drugs in the first place or become reliant on them once they start. We’re coming up on a hundred years of Alcoholics Anonymous, one of the fundamental tenants of which is, “let’s go to a meeting; there will be other humans there.”

If you needed yet another reason to behave decently to your children, helping them avoid the unadulterated misery of drug dependency as adults might be a good place to begin. Would it be too much of an exaggeration to suggest that yelling at a child for not knowing her multiplication tables has something in common with isolating a rat in a cage and offering the lonely animal water laced with pain killers?

References: