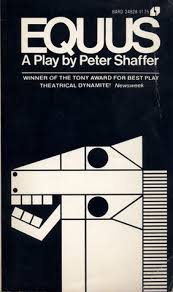

Alan Strang, the protagonist of Peter Shaffer’s Equus, commits an act so heinous as to impress theater goers long after the final homeward bound subway ride. Critics view the text as “Shaffer’s exploration of the way modern society has destroyed our ability to feel passion.” They write of Alan’s psychiatrist “[struggling] to understand the motivation.” Whereas I have a simpler insight: Alan is unable to perform with a willing sexual partner. It is his guilt and shame that allows him to implement the unspeakable crime.

Alan stabs six horses, blinding each of them.

Proponents of guilt and shame suggest that the unsavory behaviors of adolescents are kept in check by their concern for the disapprobation of their parents. Mother wouldn’t approve is supposed to curb underage stolen sips of alcohol and inept decisions about getting into cars. Then why are so many of our young people drinking alcohol and hopelessly getting into cars? Guilt and shame—like opioids—must be dispensed in careful doses. If the quotient of guilt and shame surpasses a minimal level, then the negative behaviors associated with guilt and shame far exceed any likely constructive benefits.

Because, as always, it is the relationship between parent and child that makes all the difference. Mom wants me to feel bad about my looks, my ability, my behavior runs out of steam long before dad loves me just the way I am and wants me to have a good sense of myself.

We’re not half-way down the page before I hear chirping: Kids who think too much of themselves are more likely to behave with thermonuclear wretchedness than kids who are kept in check with constraints. I disagree. Buy me, get me, I want it now is a result of parents who don’t get it. Kids who act out atrociously have unmet needs, not inflated self-esteem. Giving a child everything she screams about, allowing a child to behave like a Tasmanian Devil are what happens when a child isn’t connected. The very phrase “acting out” is about, well, acting out. Because the child’s interior essentials aren’t being met. Who would sneak out, drink alcohol, get in a car, engage in dangerously stupid epic behaviors if their needs were being met at home? Every no has to have a yes. And the yes has to be about connection.

Why do wealthy kids who “have it all” sometimes lie, cheat, steal, drug, drink, and underperform? Because having it all missed the it by a lightyear. Kids go out, act out, drop out because what they have in their home and in their relationship with their parents isn’t getting it done.

Why do kids who have nothing material—the successful types—credit the person who was “always there for them,” who “showed them the way” with whom they could “talk about anything”?

Family dinner is negatively correlated with kids who end up with substance use disorder. It’s not the mashed potatoes and green beans that keep kids off Schedule One drugs. Caloric intake doesn’t predict addiction. Family dinner is a proxy for–wait for it: families–to hang out without judging one another, without making anyone feel bad for being who they are.

Speaking of correlations, the curriculum of good recovery programs allows clients to overcome guilt and shame. Admittedly, folks overcoming substance use disorder typically have lots to feel guilt and shame about but there’s a chicken/egg issue here: did the bad acts cause these folks to feel bad? Or did the guilt and shame from childhood cause the addicts to commit the bad acts?

Guilt and shame are dirty pool by parents who, charitably, don’t know any better. At worst, guilt and shame lead to horrific outcomes. We all have so much for which to be thankful. Let’s share the joy, minimize the guilt and shame. And help keep our kids out of cars–and stables for that matter–for the holidays.

2 thoughts on “Horse Sense”

My favorite line: AKids go out, act out, drop out because what they have in their home and in their relationship with their parents isn’t getting it done.

David,

I read your posts weekly and follow your advice religiously. But sometimes I feel the need to push back a bit.

Specifically, I question your point here: “Who would sneak out, drink alcohol, get in a car, engage in dangerously stupid epic behaviors if their needs were being met at home? Every no has to have a yes. And the yes has to be about connection.”

That clear correlation you’re making between cause and effect suggests that parents are ultimately responsible for the behavior of their children. And while I might agree with that on a practical level (parents are responsible for their children, therefore parents are responsible for their children’s behavior) I don’t agree with it on an absolute level.

Good things happen to bad people. Bad things happen to good people.

Good children happen to bad people. Bad children happen to good people.

I MIGHT be the cause of my child’s bad behavior. Then again, I MIGHT NOT be.

I think that line does struggling parents of misbehaving children a disservice.

“Every no…” does not have “…to have a yes” any more than every “…yes has to be about connection.”

It just ain’t that tidy and you’re just not that sure. Neither am I…