On our morning perambulation, Langley and I could not help but notice three ginormous trucks and a dozen scurrying workmen. Closer inspection revealed tee-shirts emblazoned with the FPL logo. “Good morning” I shouted above the clamor of screaming vehicles. “Good morning,” responded several of the electricians who were not in buckets suspended fifty feet in the air.

“Did you see the Dolphin game?” I asked.

“Yes, you’ll have power tonight” came the reply.

Even by my low standards of linear communication, this exchange plopped me squarely into befuddlement mode. The sensible answers to “Did you see the Dolphin game?” are “yes, how depressing” and “no, but I heard they got blown out in the fourth quarter.” I appreciate a non sequitur as much as the next fellow, but “yes, you’ll have power by tonight” impressed me as the response to a question other than, “did you see the Dolphin game?” “Will I have power by tonight?” might be an example of one such question.

It occurred to me that perhaps my inquiry had been muddled by commuters who—once again—had neglected to account for the possibility that there might be traffic in Miami and were red-lining through my neighborhood at deadly speeds. Langley and I took several steps closer to the workmen. “Did you see the Dolphin game?” I repeated.

“Oh, yeah,” said a guy smoking a cigar. “How depressing.”

“I didn’t see the game,” said another man with a hard hat and thick gloves. “My wife said the Fins got blown out in the fourth quarter.”

We all nodded morosely. “But let me ask you something” I said. Why did you say ‘yes, you’ll have power by tonight’ when I asked if you had seen the Dolphin game?”

The man with the cigar spoke. “We didn’t hear you.” Okay, now there’s a step in the right direction. That makes sense. “But we just assumed you were asking if you’d have your power back. That’s all anyone ever says to us. You’re the first person to ask us anything other than when you’ll have power.”

I was somewhat surprised. Admittedly, urban centers are not known for neighborhood-y virtues. No square dances or barn raisings on the syllabus. Still, have we come so far from “Howza family?” and “How ‘bout them Dolphins?” Has the default value become treating people like vending machines? Don’t most people say, “Hi, howareyou?” before launching into “When will the power be back on?” Apparently not.

“… I find myself incapable of believing that all that is wrong with wanton cruelty is that I don’t like it” suggested Bertrand Russell leading to any number of productive late-night conversations. Similarly, I can’t believe that it’s okay to treat FPL employees as if they were ATM machines. But, just because I find rudeness offensive doesn’t mean that rudeness unequivocally IS offensive. So, here are some simplistic arguments for treating your friends and neighbors decently. First and foremost, they might return the favor (cf: “golden rule” alluded to by every religious tradition ever.) Treat people pleasantly and chances are they’ll be nice in return. Secondly, you’ll feel better about yourself.

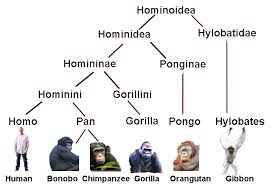

FPL employees are apparently shocked (sorry) to be acknowledged as fellow inhabitants of our genus and specie. Frequently these blue-collar folks are overlooked, considered to be automatons of some kind. “Will the power be back on by tonight?” is the most common query they hear. Questions about their health, their families, or their defective football teams are rare.

Your children will benefit from your largesse by knowing that you, their parent, value everyone—even people who work for a living. Your children will understand that they themselves have value whether they grow up to be employees of utility companies, moral philosophers, or business magnates. Being nice to working people will not increase the likelihood that your children will grow up to work outdoors.

As I am not the first to remark, our civilization is moving away from reliance on, or appreciation of, human interaction. The “cashier” at the market is no longer a neighbor, a member of your community. The cashier is just as likely to be a machine of some description with a syrupy recorded voice that makes me want to put a fork in my ear. But talking to the check-out machine–“say ‘hi’ to all the little zeros and ones at home”–will not teach your kids common politeness. Modeling for your kids to “give all men thy ear, but few thy voice. Take each man’s censure, but reserve thy judgment” will have better consequences. So will walking into the bank to say hello to the teller. So will chatting with FPL employees about something other than when the power will be back on.

Children learn what they live. Let your kids live with common politeness and old fashioned virtues. I promise your kids won’t grow up to live in the 19th century as a result of having values of some time ago. The nicer you are to other people, the nicer your children will be to you. Besides, a distinct advantage of living in the 1800s was that the Dolphins didn’t yet exist.

One thought on “Shocking”

Very apropos. Our electric utility (PG&E) has announced that they will be shutting off electricity to several hundred thousand people (or customers) in more than half the counties in California starting in the early hours tomorrow (they don’t want to be responsible for sparking fires as hot dry winds are forecast for Wednesday and Thursday October 9-10). They alert ed people that to find if your house/school/business will be without electricity for several days, use their website. Of course their website is not responding as several hundred thousand people are trying to connect to it, and feel they must do so repeatedly to see if the news has changed in the past 5 minutes.

But our friendly, helpful neighbors are exchanging emails asking whether our neighborhood will be affected. Their helpful information includes the fact that the PG&E website is not responding and so they don’t know what is going on. Several people have also confirmed that they don’t know what is going on, either.

So it does seem to be true that people can join together in response to emergencies like prospective electrical outages. We value each other and care about what happens in the neighborhood and so join together to share our ignorance.