I have been accused of championing mediocrity. In these weekly newsletters. Ouch! Untrue! These denunciations follow a familiar pattern: you disparage highly selective schools, you tell us it’s okay if our kids don’t get As in advanced math courses, you suggest that a good relationship with our kids is more important than where our children go to college.

Aren’t you just suggesting that parents should value ordinariness in our children?

As Curly—my favorite of the Stooges suggested, “I resemble that remark.”

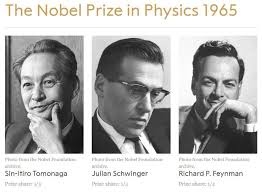

To be contrary: I appreciate excellence. I’m in favor of exceptional accomplishments. Nothing makes me happier than (re)watching Joan Benoit win the 1984 Olympic marathon or Henry Aaron smacking a baseball into the stratosphere. I am overjoyed that Jacob Kiplomo crushed the half marathon record in Barcelona in February, covering 13.1 miles in 56:42 or four minutes twenty seconds per mile. I’m just pointing out that if your child isn’t the next Richard Feynman (safe bet, they’re not) that your best strategy is to love them unconditionally for who they are not for what they do. It’s great that Feynman shared a Nobel Prize in physics for his “fundamental work in quantum electrodynamics with deep-ploughing consequences for the physics of elementary particles.” It’s just that there’s only one Nobel Prize in physics awarded each year and nobody reading this blog (or writing it) understands any of the words quoted above.

Honestly, if I thought you could make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear, I would write—as so many of my colleagues do—about how you can change your child into who you want them to be rather than who they are. Bippity, boppity, boo! Your son who loves reading now cherishes athletics. Your daughter who excels at creative writing now wants to fill in worksheets, your kid is working on quantum electrodynamics and the physics of elementary particles. Encourage, yes. Destroy your connection with your child by communicating, I would love you more if you got an A in algebra II, not so much.

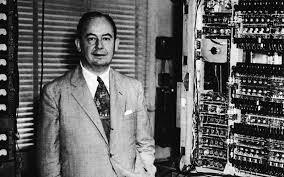

To further clarify my affection for the best of the best, I offer the following vignette about a guy who spoke fluent Hungarian, French, German and English, could get by in Italian, Yiddish and had a working knowledge of Spanish. Oh, yeah. He also learned Latin and Greek. By the time he was six.

But language proficiency was the least of his otherworldly abilities. As Einstein was the greatest physicist of the 20th century, Jonny Von Neumann was the greatest mathematician. I have written elsewhere about Von Neumann’s prodigious arithmetic prowess and his contributions to game theory, artificial intelligence, and the Manhattan Project. Many scientists suggest that Von Neumann’s contribution to the development of the atom bomb was the most significant. Von Neumann has been described as “the greatest mathematician that no one has ever heard of.” Unlike the actual accomplishments mentioned, the following story may be apocryphal.

Von Neumann is at a gathering of other physicists and their families. At the party are a number of folks who have won or will win the Nobel Prize in physics. Von Neumann is sitting on the floor chatting with the three-year-old son of a colleague. Both Von Neumann and the child are animated, smiling, conversing freely. Clearly, they are enjoying one another’s company.

One of the Nobel Prize winning physicists looks over at Von Neumann interacting with the child and remarks, “maybe that’s the way he talks to all of us.”

At the risk of “explaining the vignette,” the distance between the cognitive capability of Von Neumann and the other Nobel Laureates is so great, it makes the difference between Von Neumann and the child seem comparable. It is said that Von Neumann could listen to a PhD defense and explain how the problem could have been solved more simply. Brilliant mathematicians who had been working on a proof for 18 months were frequently shown up by Von Neumann who, until that day, had known nothing about the entire branch of mathematics.

Here’s my take away: If the arguably smartest person who ever lived—were you invited to the Institute of Advanced Studies at Princeton? All right then—can enjoy having a conversation with a three-year-old, then so can you. Rather than focusing on getting your kids to do things, you can just love the fact that you have a three-year-old to whom you can read and teach to ride a tricycle and explain how birds fly and what a fascinating wonderful place the world is. And there’s no reason to change the attitude of wonder, excitement and joy as the children get older. Every day can be a hilarious, exuberant connection.

Even if your kids don’t grow up to be able to multiply eight digit numbers in their head, speak eight languages, or get a Nobel Prize in physics.