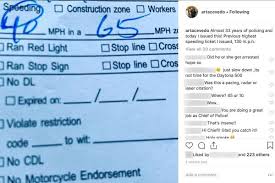

Having heard on the radio that The Irreducible Needs of Children had just been published, I emphatically sped across town. My flouting of conventional driving mores will be understood: Stanley Greenspan and T. Berry Brazelton are among our country’s most profound thinkers on child development. I didn’t want to arrive at the bookstore and stand in a lengthy line only to learn that the book had sold out. I envisioned long queues of anticipatory parents and professionals. I felt certain that The Irreducible Needs of Children would be as popular with parents as Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban was with kids. I anticipated wrestling struggles over the last copy after hundreds of books had flown off the shelves.

Needless to say, I was grievously mistaken. Once the clerk was able to decipher my breathless exhortations, he said, “yes, I think I remember that book coming in. Let me check.” A trip down a dusty stairwell lit by a bare light bulb produced the treasured if lonely volume. Apparently few folks in Miami shared my concern about either the availability of the book or its contents. Ariana Grande need not worry about competition from developmental psychologists or child psychiatrists.

I enjoyed the book though, learned a lot. I’m also glad to know that I’m not the only one thinking about where happy and sad kids are more likely to come from. Indeed, my life-long obsession with how to raise healthy kids in our unhealthy world has suggested some themes. For example, parents tend to look around at how other kids turn out. As if the starting line were inviolate. Kids differ—by gender, height, a host of genetic and environmental characteristics—yet parents opine about Alex’s valedictory talk or Robin’s winning goal. Why isn’t my child someone else? Circumstances be damned! The heck with reality.

Children on one side of town lack food, medicine, appropriate education, opportunity to grow into the adults they deserve to become. These kids may want books, libraries, intellectual stimulation. These kids are not heard. They are not able to express or fulfill their need for sustenance for their bodies or their minds. At worst, kids are forced to fend for themselves as parents have to work rather than provide nurture and care.

One hears stories of these children misbehaving to get what they need—selling drugs to earn money because jobs that pay a living wage are not available; stealing food, falling asleep in class. The worst forms of abuse are those that deny kids the chance to be who they are. No child should suffer inappropriate touching. Physical and sexual abuse take generations to repair.

And what of children on our side of town? Are the similarities actually profound? Food insecurity is not a concern. Our homes have discretionary income for books. But do we also deny our children the opportunity to be who they are? Are we forcing them to be athletes when their preference is to be students? Or insisting that they be studious when they would prefer to run around? Is the oppositionality prevalent in our kids resulting from their needs not being met, from not being heard? Could the “f*ck you mom, it’s all your fault, I hope you die, you f*cking b*tch” kids from all locales actually be coming from the same place? Could the result—out of control, angry, depressed, acting out kids who refuse to comply with any and all parental suggestions—be from the same psychic place if not the same physical neighborhood?

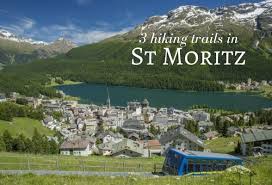

“Rich or poor, it’s good to have money” my grandmother pointed out. Whether your family summers in St. Moritz or the community center, listening to your children–knowing who your kids are–like the Swiss flag, is a big plus.

And you don’t have to endanger pedestrians to give your children what they need.