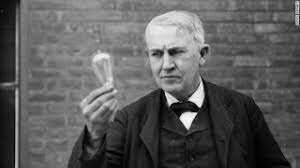

Just as Edison is frequently invoked as knowing a thousand ways not to make a lightbulb, I am intimately familiar with how to run a marathon so as not to qualify for Boston.

Having had the good sense to turn 50 and noticing the requisite time necessary to get a spot in that famous event, I memorized the eight times tables. At two miles, I need to be at 16 minutes, at three miles, 24 minutes and so on. (No numbers were harmed in this rendition although a little rounding has occurred to keep the story moving.) At 20 miles I was right on pace—eight times 20 is 160 minutes or two hours, 40 minutes. Nice! Awesome! Feeling good! Six miles to the finish and accomplishing something I had been working on for decades. What could possibly go wrong?

What went wrong was that the 21st mile, inexplicably, took several seconds over eight minutes to cover. Then the 22nd mile took eight minutes and 20 seconds. I gritted my teeth, gave it all I had, reached deep into the recesses of several sports cliches, and ran the 23rd mile in eight minutes and 40 seconds.

I am now a full minute behind the requisite pace. Close only counts in horseshoes and hand grenades. Miles 23 through 26, though they seemed faster, were actually closer to nine minutes. I finished a full two minutes off the pace, did not qualify—again!—to run Boston, and went on with my life.

But what is of note is the way runners and non-runners react to the rendition of the experience. Non-runners say, “why didn’t you just run the last three miles at seven minutes and forty seconds per mile? You were 60 seconds behind. All you needed to do was make up that time. Sixty seconds divided by three is 20. By running 20 seconds per mile faster for the last three miles you could have achieved your dream and qualified.”

Whereas my fellow runners hearing how the wheels came off at the end of the race just nod their heads knowingly and say, “Yeah.” The wheels came off; then the carburetor fell out. Followed by the doors coming off and the car bursting into flames. Then I think my legs exploded. Fellow runners know what can happen after 20 miles. Fellow runners get it. Non-runners don’t.

Which is fine. Not everybody has to be a runner. Indeed, after 40 years of sweaty early mornings, I’m not sure I would recommend this particular past-time. I’m just pointing out that compatriots can relate to success or failure or striving or a good story whereas if you haven’t run 26 miles in our shoes you might not be able to connect on the same visceral level.

As parents, you know your child’s journey. Or you should. And you can supply the narrative. Which is where you have tremendous latitude. You can construe any behavior with disparate interpretations. If your 17-year-old son isn’t putting away his laundry, there are any number of ways you can approach this unfortunate reoccurrence. Is your son cognitively impaired? (Probably not, you had him tested in elementary school.) Have you not made your wishes clear? (No, you have mentioned your desire that the laundry be put away frequently, emphatically, and in many Romance languages.) Is your child physically incapable of moving the laundry from the basket to the drawer? (Again, no. You would have noticed the charge on your insurance bill for the wheelchair.) Is your child just an insensitive, atrocious person who doesn’t appreciate how hard you work and shouldn’t he be doing his own darn laundry at 17 years of age and shouldn’t he have been diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder in addition to oppositional defiance just like his father and that’s why I divorced his pathetic self all those years ago? (Possibly. And I’m with you: your ex wasn’t a good match for you, no argument. But I’m going to take the conversation in another direction.)

It’s the relationship that matters. And an open, honest, difficult conversation about the connection between parent and child can only move you and your seemingly recalcitrant son in the right direction. Honestly, I don’t know why he isn’t putting his laundry away. Some children greet their hard-working parents with the table set, dinner cooked, and the laundry washed, dried, and put away. These children thank their parents for providing for the family and strive to make mom and dad proud and happy.

Okay, I just made that up. There are no children that gracious in 2023, not that I’ve ever met or heard about anyway. A 17-year-old who says “I appreciate everything you do for me, mom, I hope you like the dinner I made” is unlikely. The science fiction and fantasy section of blog posts is only a few clicks away, but there is a continuum of kids who help out. I think it’s the relationship that makes the difference.

A kid who resents his parent—they’re always telling me to do stuff that I don’t want to do and that they don’t do themselves, they only care about my grades so they can tell their friends what good parents they are, they don’t know me for who I am at all—is less likely to put their laundry away than a kid who feels seen and heard and appreciated for who they are.

I’m not suggesting you have to run 26 miles with your child to know just how painful and glorious their journey has been. But going for a hike, say, or having a conversation about responsibilities around the house, might be a good place to start.

2 thoughts on “Running the Laundry”

Not to pick nits (okay, to pick nits): almost also counts in nuclear war. In fact, you don’t have to be very close at all. Just sayin’…

I always love your comments, John. Your blog is also wonderful. I never miss an issue.